I’m going to be on Marketplace next week talking to Kai Ryssdal about the labor market. I won’t exactly sound upbeat.

The unemployment rate—which is the North Star for gauging the labor market’s health—is fine. In fact, by historical measures, this is about as good as it gets. But the hiring rate has cratered, and from its perspective, the labor market right now looks like it’s in the middle of a deep recession.

So are we in a recession?

I don’t really like that question. But first, some context about what’s going on.

It was the best of times,

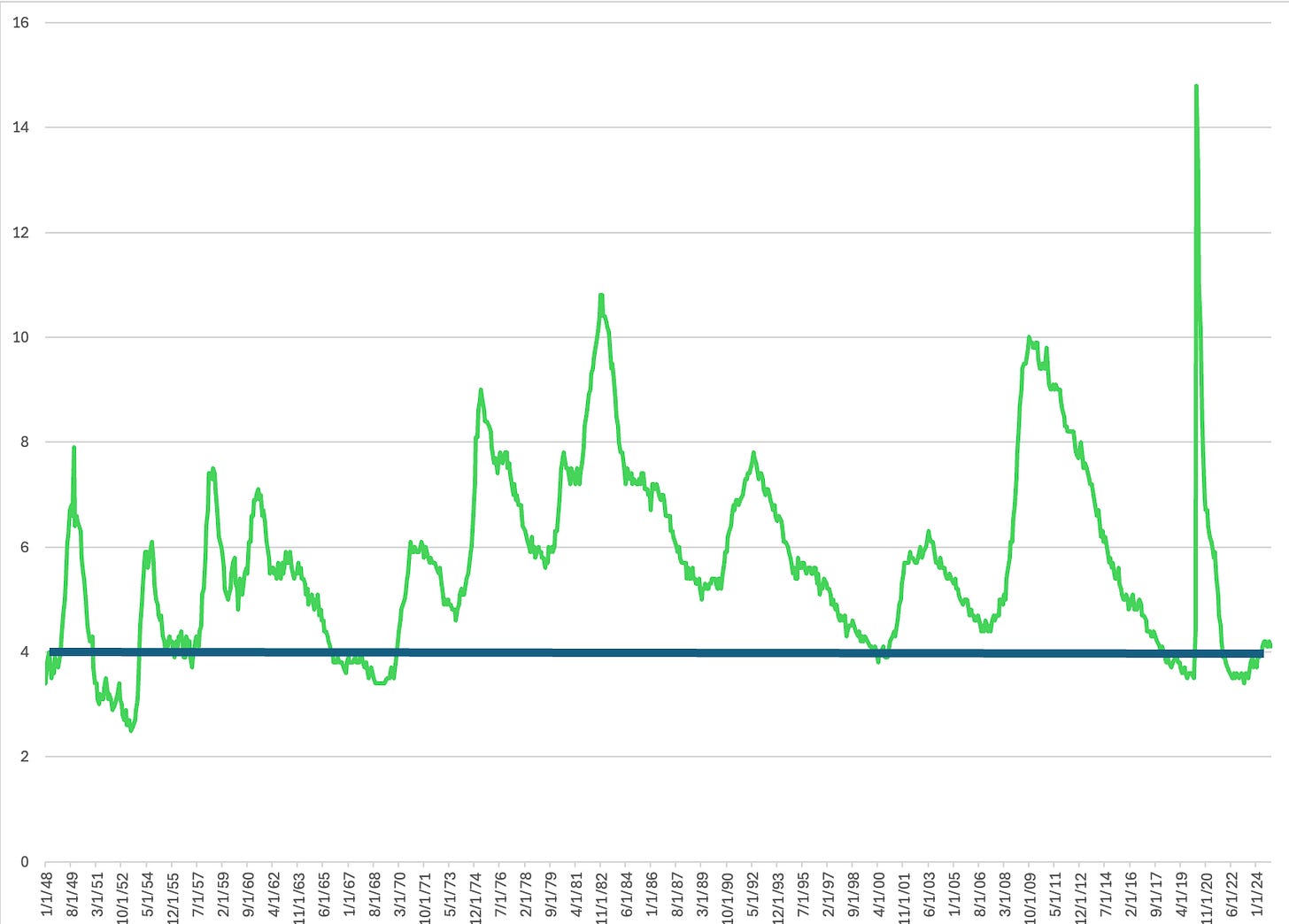

First, here’s the unemployment rate for as long as we’ve collected consistent, comparable data monthly data (back to 1948) . The unemployment rate is the share of workers who do not have a job but are actively looking for work (a retiree wouldn’t be unemployed, even though they aren’t working, because they don’t want a job and aren’t looking for one).

The unemployment rate measures whether the economy is producing enough jobs for the people who want them. During a recession, when the economy slows down, unemployment jumps up. You can see the peaks marking every recession since 1948:

The bold, horizontal line is the 4% mark. Being at or below 4% is considered “full employment,” and it’s about the best the economy ever does. And you can see in the figure, the economy can go decades without getting or keeping unemployment that low. If you look where we are now, we are hovering around 4%.

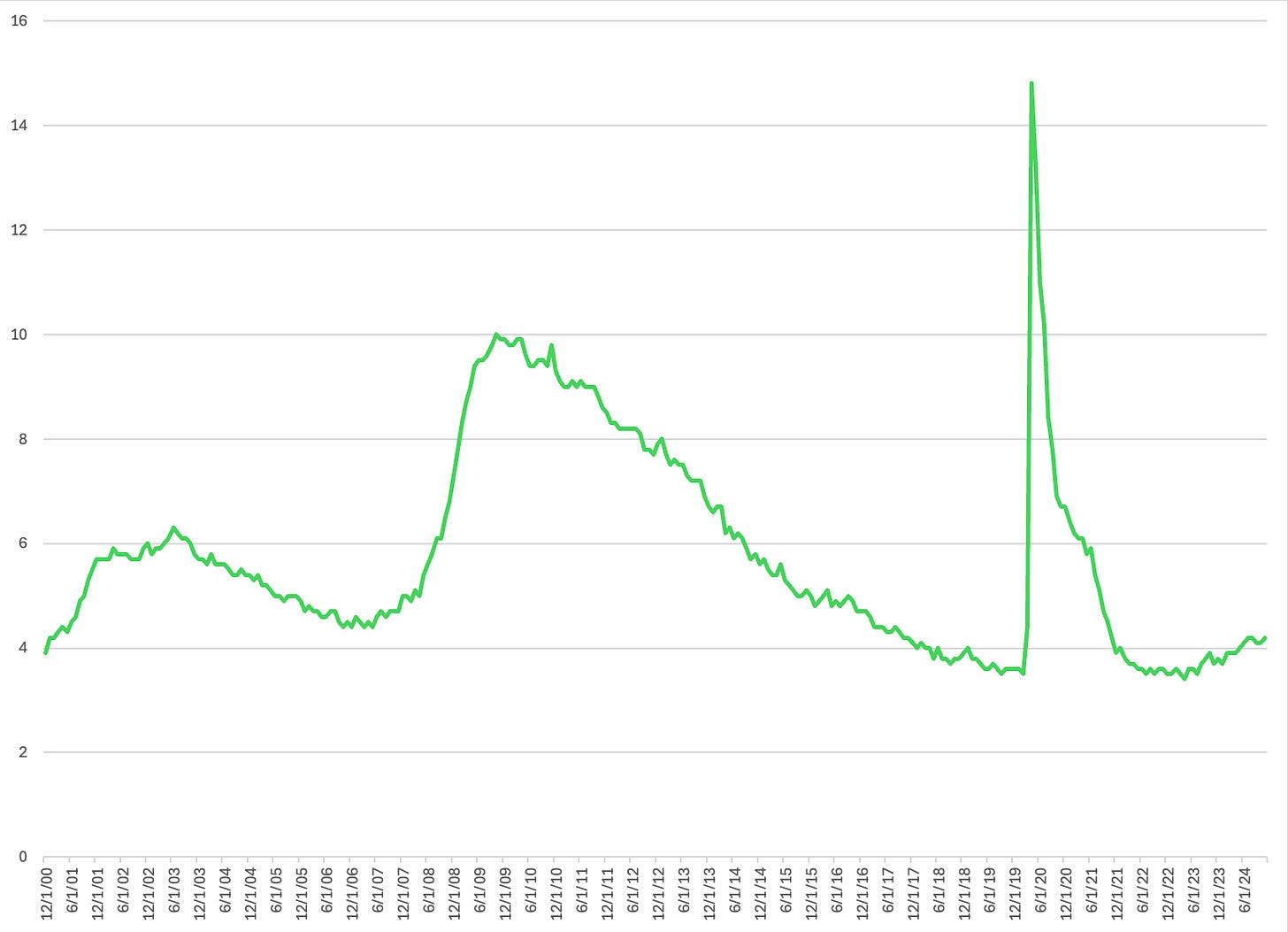

So now let’s zoom in. Here’s the unemployment rate since 2000. The first peak is the 2001 recession, the second peak is the 2007-2009 recesison aka the Great Recession. And look at how long it took for unemployment to fall after that recession—it earned its title. The third peak, which is more of a spike, is the pandemic.

Over the last few years after the pandemic, unemployment has been low but is slowly creeping up. It is still better than where we spent the last quarter century (and really the 35 years before that).

Seems pretty good!

It was the worst of times.

Now let’s look at hiring. The hiring rate is the percent of people hired in a month as a share of total employment. It would by definition include the hires of people who switched to a new job as well as the hires of people who were looking for their first job.

The data on hiring are only consistent and comparable back to 2000. In recessions, the hiring rate falls as the labor market’s churn slows down. You can see these ‘falls’ in the 2001 recession, and again the fall in 2007-2009 recession. The pandemic you can’t see the same way. All the job losses of the pandemic were in a single month, and about a third of those jobs came back within two months.

But what you can see after the pandemic is fall that looks like a recession. Hiring has been declining for nearly three years.

If I hadn’t shown you the unemployment graph, but told you what recessions looked like in hiring data, you’d be right to assume that we are currently in one.

The hiring rate at the end of the year was 3.3%. As I pointed out in my Bloomberg column a couple weeks ago, the hiring rate has been exactly 3.3% in 22 different months before now. And on average in those months the unemployment rate was 8.2%, double the 4.1% it is now.

It was the age of wisdom,

Unemployment trumps hiring. So even though hiring doesn’t look great (or feel great, for that matter) there’s no rule that says it can’t turn around and improve, or that unemployment has to go up.

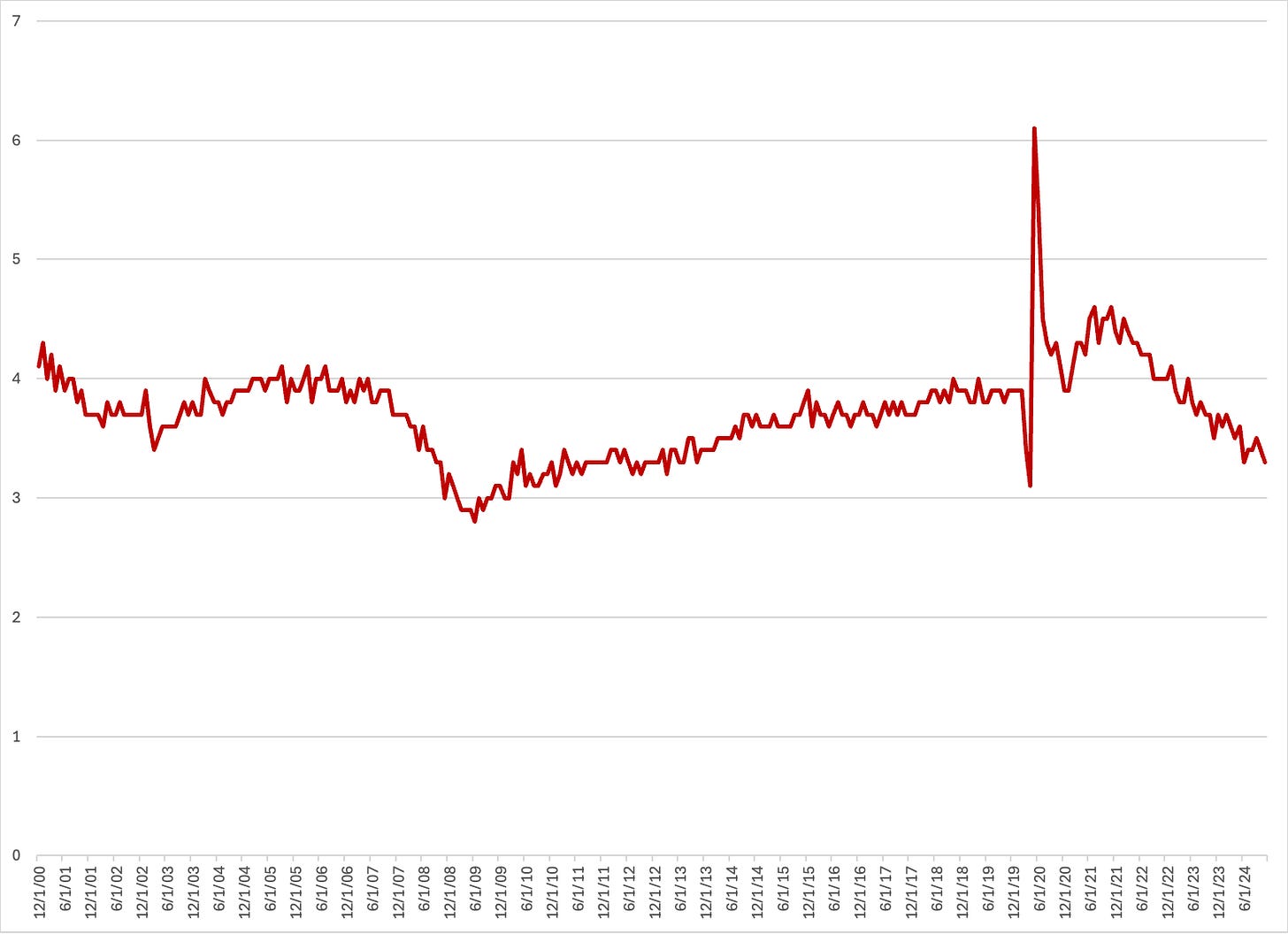

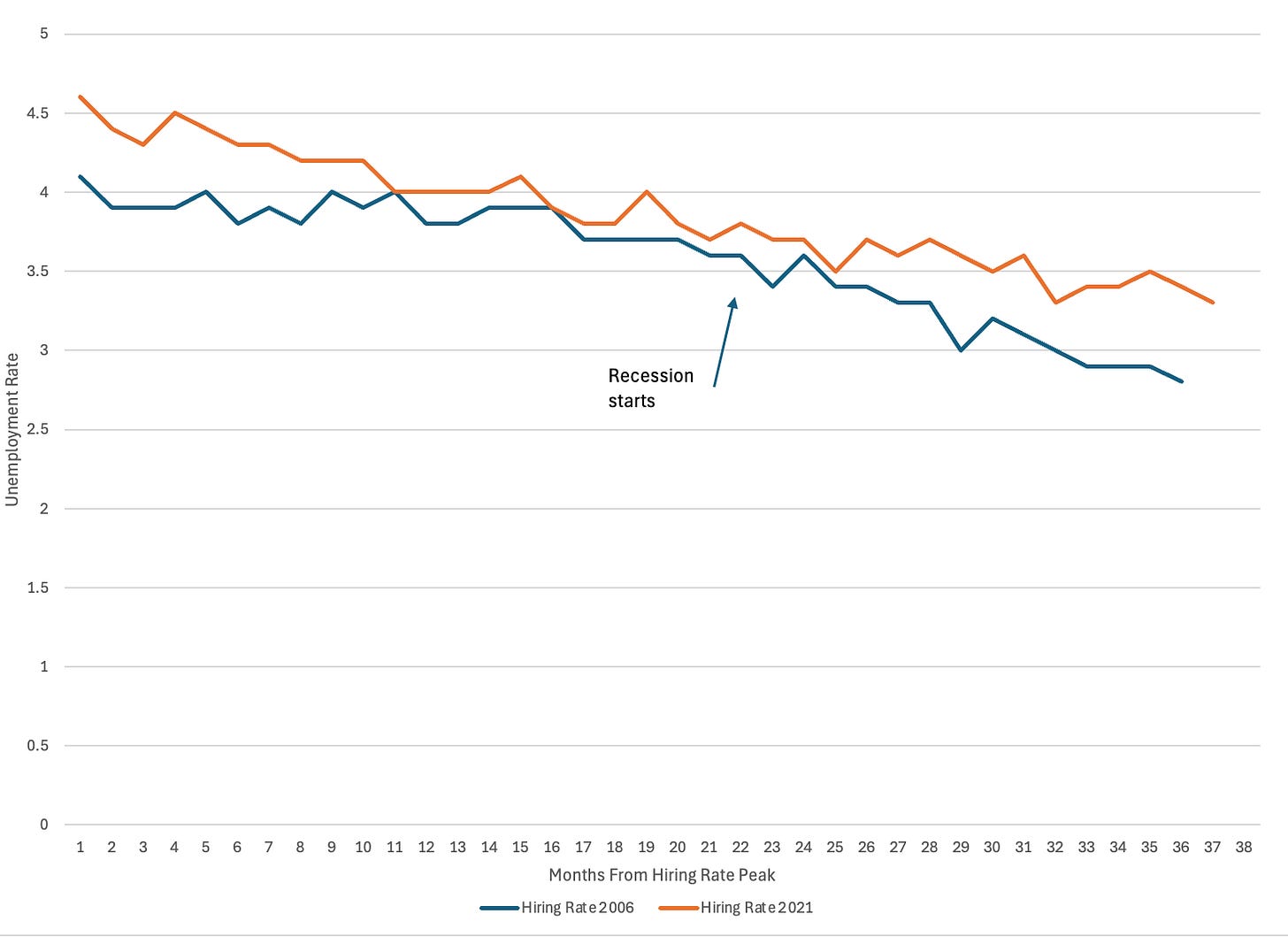

You can see this in the graphs I just showed you. Let’s look at hiring again, only let’s realign the data so we are comparing the two most recent falls from their peak. Hiring fell from July of 2006 to June of 2009 during the Great Recession. In our timeline, it’s been falling since November of 2021. This figure shows those falls based on the month from peak rather than the calendar month.

They’re identical—hiring fell by 1.3 points in both cases.

I pointed out in the figure the month that the recession of 2007-2009 officially started, December of 2007. It doesn’t really “show up” in hiring; the trend doesn’t change even as the economy tips into recession.

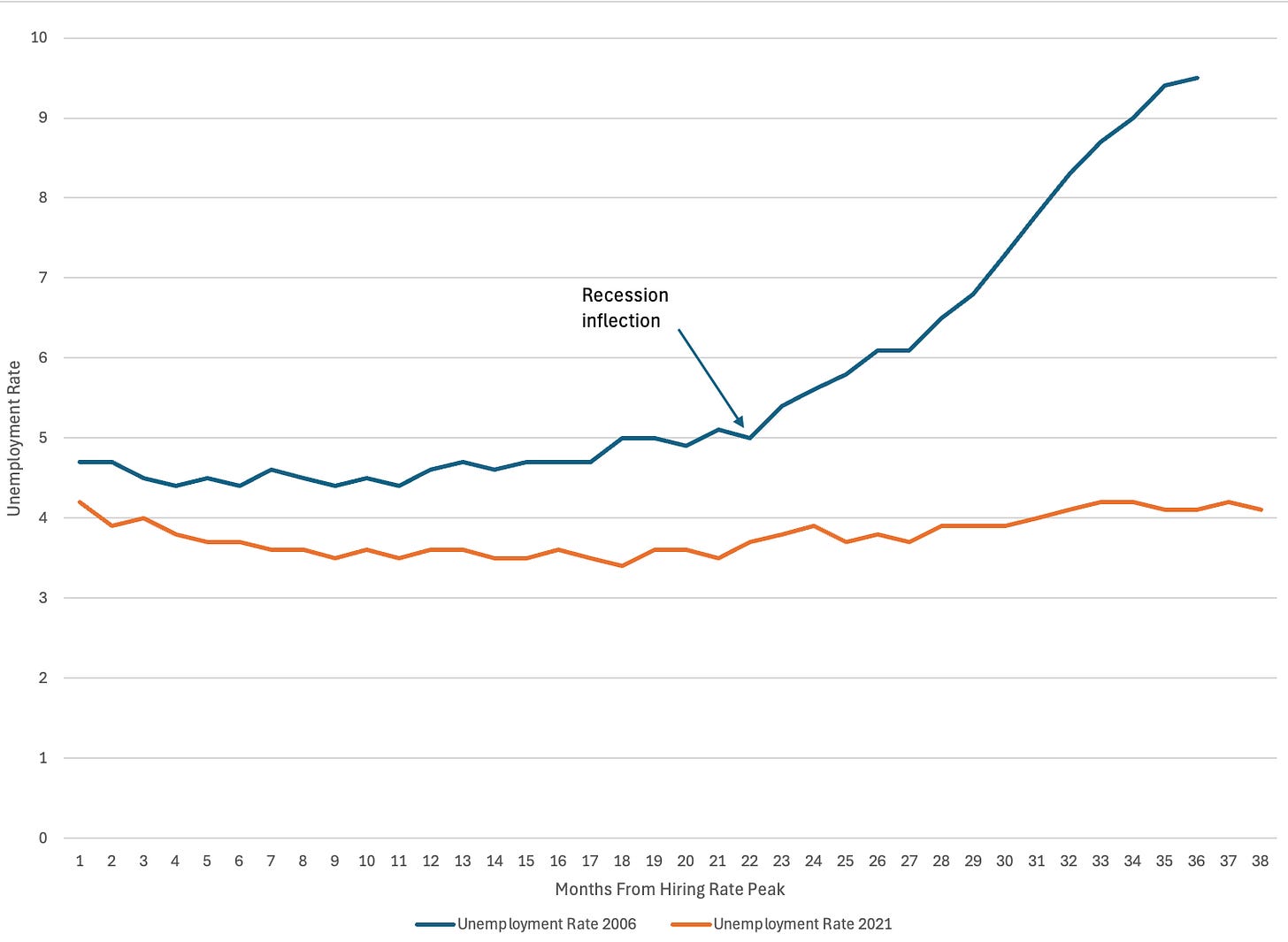

What did change was unemployment. In the next figure, I show unemployment in the same periods, also realigned to start at the peak of hiring.

In 2007-2009 recession, unemployment was low and slowly ticking upward when it hit a recession inflection—one last month of a tick down before it went up and up and up. And it really took off. It took less than a year to nearly double. That first month of the recession is obvious here.

And that’s the point. Today we haven’t seen an inflection, just the slow tick up.

We don’t know where the orange line goes from here, and that’s kind of the point. It doesn’t have to go up.

It was the age of foolishness.

So are we in a recession? The reason why I don’t like that question is that makes the economy about predicting status rather than predicting health. It squishes all economic data into “recession level or not” or “recession predictor or not.” I am sure someone out there is predicting that based on the hiring rate we are in a recession.

But that prediction is two-dimensional. The problem with a low hiring rate isn’t that it could predict a recession, but that it could make a recession very bad, very quickly. The substantive problem isn’t whether we are in a recession but how severe it can be.

The Fed has said as much. We recorded the Marketplace earlier this week, and the day after we recorded, Jerome Powell the Fed Chair, said this at his press conference:

“Well, the things we watch we discussed earlier, one is that there's a low hiring rate. And so, that if there were to be a spike in layoffs, if companies were to start to reduce headcount, you would see unemployment go up pretty quickly because the hiring rate is quite low. So, that's one thing we look at."

An already low hiring rate is an accelerant, it’s gas on the bad economy fire.

Go back to the first figure that showed 75 years of unemployment peaks and troughs. A recession is *always* coming. Our economy is cyclical. It’s not a question of if, but when and how bad.

I never make predictions, because I never want to give up on policy being able to make a difference. What I told Marketplace is that the labor market is at the edge of a cliff with a strong wind at its back. It’s too close to the edge to feel comfortable, but it’s not over yet.

Tomorrow is the alleged start of a trade war, declared on our two largest trading partners and allies. Policy can make a difference for good, to stave off those recession inflections. But it can go the other way too.

I’m hopeful about the future, but that doesn’t mean I think there isn’t any pain on the horizon.

PS When do we find out if we are in a recession?

Fun fact: we could be already, technically!

When a recession is “declared” it’s always backdated. The start of the 2007 recession, for example, was announced at the end of 2008.

The group of economists in the business cycle dating committee at the National Bureau of Economic Research who call recessions are looking for when economic activity peaked. Their aim is to establish a benchmark by which to compare across recessions. It can’t be just one bad data point or indicator; their announcement carries a lot of weight. So they wait for more and more data to arrive, for every data point to become a clear trend, and then they call it.

By the time they do, the economy is doing poorly and everyone *knows* we are in a recession because they can feel it and see it. So the committee ends up being a post hoc “by the way, the mess we are in started in February” announcement.

That’s good. If they called recessions too quickly or too early, they could risk turning a dicey moment for the economy—not great, but not terrible—into an actual downturn. Every blip becomes a recession. They are much more cautious, which is good. It gives policymakers a chance to act in response to make sure the blip stays a blip.

All of which is to say, we don’t get a heads up when the economy goes bad, we get a confirmation after the fact.

How do the formation of microbusinesses affect employment statistics. For example if a person is looking for work as an employee, and doesn't find it, but then they start a microbusiness as a subcontractor or as an independent service provider, they depart from the unemployment statistics. But are they counted as "hired" when they work for themselves or as a non-employee subcontractor? Subcontractors and microbusiness owners are a significant part of the workforce, do official statisticians count them the same way?

This is an unusual new world, but hope you won't say UI is an indicator of anything- it's not. Claimants are disappearing, people are not claiming UI anymore, (benefits are vary low in about 14 states, (Recipiency Rate is at an all-time low). Those that do claim will wait awhile before making a claim, and average duration is only about 15 weeks.

Best wishes for your interview.