The Labor Market’s Best Just Isn’t Good Enough

Ample demand for workers hasn’t delivered benefits, fixed disparities or eliminated abuses

Another from the Bloomberg vault, I wrote this piece at the start of last summer. The unemployment rate for the 12 months before had been around 3.5%, a truly astonishing low. Even though its since ticked up to 4.3%, we are at the end of a historic labor market.

I took that as the premise: this is the best the labor market has ever done, so it’s able to teach us definitively what markets alone can’t do. Policy has a job, and it’s not that often we get a clear sketch of exactly what that job is. This tight labor market was a gift for policymakers, the simplest indication of what the market will never accomplish. My call was to take notes and get to work.

Happy Labor Day, I wish you all a paid day off of work.

The Labor Market’s Best Just Isn’t Good Enough

Published May 11, 2023

The US labor market will probably never be better for workers than it is right now. As such, it sheds much-needed light on a question crucial to the country’s longer-term prosperity: What problems can the market solve, and what must policy instead address?

The short answer is that policymakers have a lot of work to do.

The prevailing wisdom in American officialdom has long been that a strong economy cures all ills. Active interventions such as raising the minimum wage or mandating paid family leave, the logic goes, kill jobs and hence should be avoided. Instead, government should focus on fostering maximum sustainable employment through broader fiscal and monetary policies, and otherwise let the labor market work its magic.

For years now, employment has been about as maximized as it gets. The unemployment rate has remained below 4% since February 2022, and it spent another 20 months there before the pandemic, marking the tightest labor market on record since the late 1960s. This has done a lot of good for workers, accelerating wage growth and helping people — including the long-term unemployed — get off the sidelines and back into jobs.

In too many ways, though, it’s not nearly good enough. Four areas stand out.

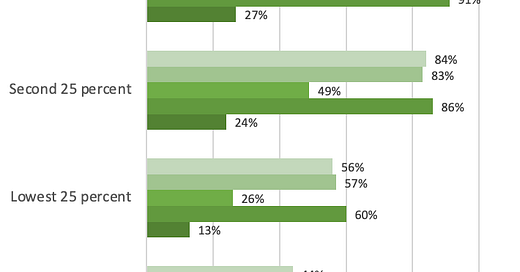

► Benefits. As of March 2022, only 13% of workers in the lowest income quartile had access to paid family leave, and 40% or more had no paid sick of vacation days. These remain luxuries reserved largely for people who are already well compensated.

Figure: Share of workers with access to benefits, by wage distribution

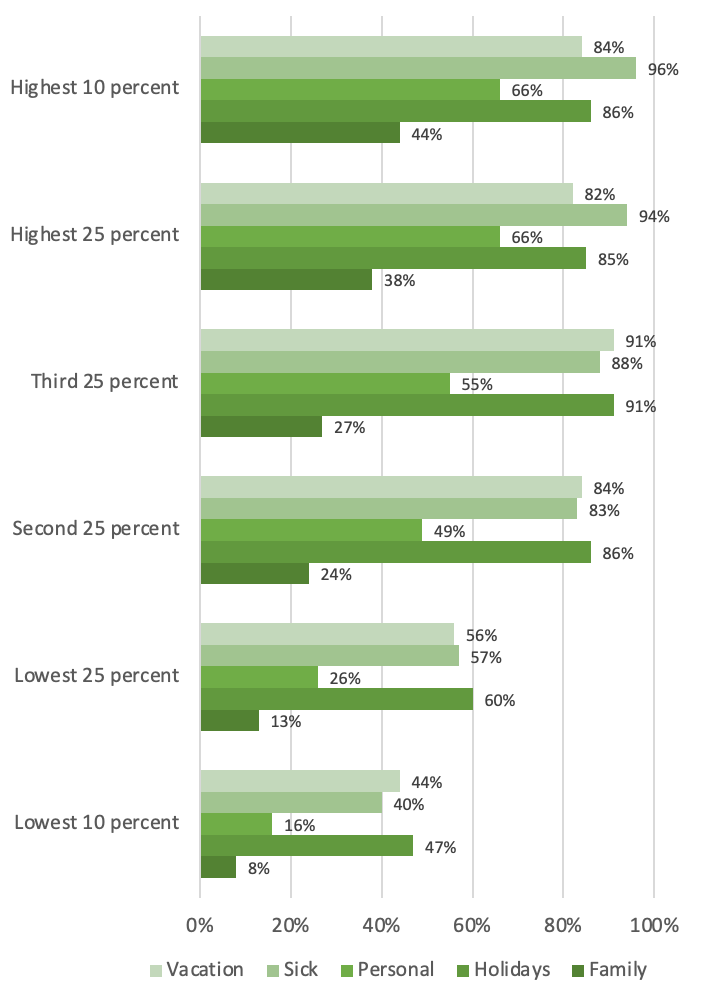

► Disparities by race and gender. As of April, the unemployment rate for Black workers stood at 4.7%, compared with 3.2% for their White counterparts — somewhat better than the typical twofold difference, but still a large gap. Meanwhile, the pay penalty for working while Black or female remains stubbornly large.

Figure: Unemployment rate by race and gender, 1954-2023

► Child labor. Government investigations found nearly 3,876 minors employed in violation of labor laws in 2022, up from 1,609 in 2017. And that’s just recorded violations.

► Wage theft. The Department of Labor discovered nearly 14,000 violations of minimum-wage and overtime rules in 2022, involving more than $150 million and 140,000 workers. And that’s with an enforcement budget that hasn’t meaningfully increased since Jimmy Carter was president.

The solution is neither elusive or original: require through federal labor standards what the market won’t voluntarily provide, and provide sufficient means to enforce those standards.

The market is powerful, but not perfect. There are limits to what it can accomplish, even when firing on all cylinders. Among the lessons policymakers learn from this economic moment, let this be a prominent one.